Felt Hats from Lancaster & the Lune Valley

Felt hats were fashionable from at least 1550 to around 1850. The felt could be made from wool and rabbit fur, but beaver felt was particularly popular.

So much so that both the Eurasian and American beaver were hunted close to extinction for their fur.

Many documents survive which tell us about hat-making in Lancaster and the surrounding areas. These have been extensively researched by local historian Christine Workman. The following information is largely based on her research and the author has generously given further advice in sharing this information with Lancaster Maritime Museum to support the exhibits on display.

Felt hats seem to have been invented in the mid 15th century in Normandy and the craft brought to London about the same time. Walloon immigrants (from Wallonia, now a part of Belgium) also brought the craft to Britain and the centres of hat making spread to Bristol, Maidstone, Kendal and Braintree.

A Merchant was there with a forked beard

In motley, and high on his horse he sat,

Upon his head a Flandrish [Flemish] beaver hat.

-From Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written in the late 14th century.

Workman cites the earliest known reference to a trade in hats in the Lune Valley to 1674, when James Bancroft of Lancaster bought wool from Sarah Fell’s own sheep stock in Swarthmoor Hall and in return he sold Quaker Hats back to her.

Hat making in Lancaster, the Lune Valley and surrounding areas coincided with the city’s ‘Golden Age’ when the port was in its heyday, around 1750-1800. Places noted for hat making were Quernmore, Over Wyresdale and Wray. Notable hat manufacturers in Lancaster in the late 18th century include John Scales, Christopher Shearson who operated on Cable Street, and George and William Braithwaite.

Population increases and migration to cities from rural areas meant there was an increased demand for hats at this time. They were becoming a fashionable item as well as a functional head covering. Tricorne or bicorne cocked hats were favoured in the 1700s, before the top hat came into fashion around 1800.

From our collections: LEFT – Photo of 2nd Lieutenant George Read, Chief Officer of the Coast Service at Morecambe, c.1864. His dress uniform includes a bicorne cocked hat trimmed with gold braid. Bicornes remained a part of military uniforms long after they’d fallen out of fashion in civilian circles. RIGHT – Beaver felt top hat made in Wray and owned by John Selby, tailor of Hornby.

How is a felt hat made?

Hat making was mostly a workshop-based industry (rather than a cottage industry) and it’s useful to understand the processes involved to see the need for a dedicated workshop.

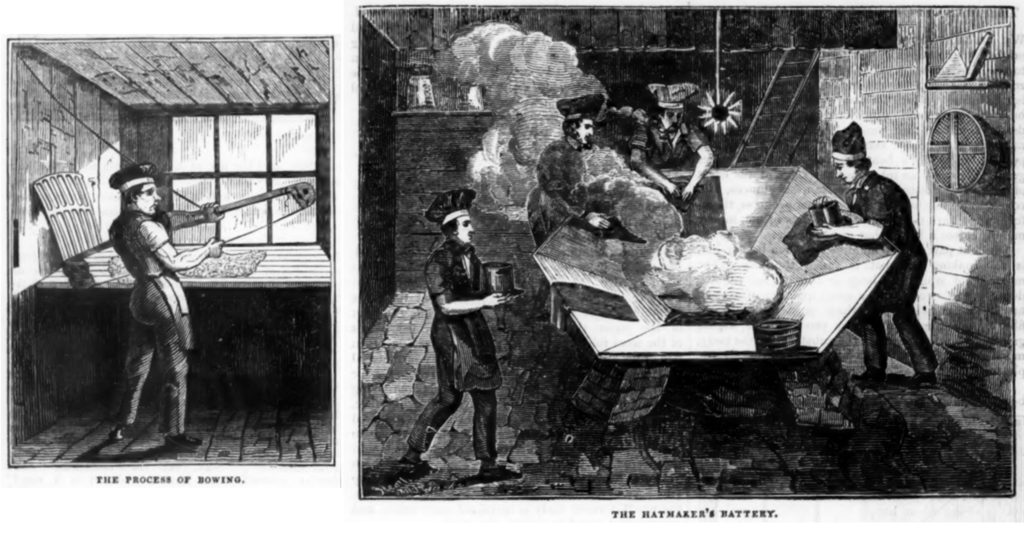

The Saturday Magazine published an article on hat making in 1835 and the two images below taken from this article help to illustrate a few of the steps involved.

- Felt is made from boiled wool. Wool fleeces were sorted and the shorter fibres were selected as being more suitable for felting.

- These fibres were then carded. Carding involves brushing the fibres between tines to ensure the fibres are smooth and aligned in one direction. This was done by hand in the late 18th century, often by women working at home.

- Rabbit or beaver fur was added. The fur was shorn off the skin and “carrotted”, treated with mercuric nitrate, which is poisonous. The term ‘mad as hatter’ refers to the shakes and mental illness which many hatters developed after working with this compound.

- Bowing is the term for the next phase of felt hat making. (Picture above left.) Wool and fur were spread out over slats in a draught-free room. A bow made of wood and cat gut was twanged by the hatter over the wool and fur. This caused it to stir up and float down into a collection of overlapping fibres. These were formed into a conical shape, called a pad. Two pads were joined to form a basic hat shape, called a body.

- After bowing came felting or planking. (Picture above right.) This was the most important part of the manufacturing process. It determined the quality and waterproof finishing of the product. Felting involved building a fire under a kettle (copper vessel) with large planks of wood placed above. These could be arranged in a sort of hexagon over the kettle and allowed each hatter to have their own working surface on which to felt the fibres. A hatter would continually dip the conical shaped body into the hot water so that the material shrank to form a felt. At the same time the hatter worked at the plank to roll the body into a basic shape, using a rolling pin.

- The body was further wetted and pulled down over a wooden or stone block to produce the required hat shape. The excess felt at the bottom after being pulled over the block was used to form the brim of the hat.

- Finally, shellac or other waxes and gums were used to waterproof the felt. This part of the process may have been done in other places, e.g. top-end finishing may have been done in cities before the hats went on sale.

There is a place, like no place on earth. A land full of wonder, mystery, and danger. Some say, to survive it, you need to be as mad as a hatter. Which, luckily, I am.

-The Hatter, Alice in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll. Hat makers in the real world often suffered from tremors, hallucinations and emotional problems caused by mercury poisoning.

Why was hat making successful in Lancaster and the Lune Valley?

Research by Workman suggests a number of factors:

- The materials needed to set up production of hats were relatively cheap and easy to obtain. A kettle (a copper vessel to boil water in), fuel (usually wood or coal, both found locally) and a water supply were essential. Some wooden planks, rolling pins and a block on which to mould the felt were also needed.

- Sheep farming in the Lune Valley and Wyresdale helped to supply the wool for felt hat-making. Sheep farming was a seasonal activity. Therefore men and women were available to be employed in hat making when not busy farming. They often had the premises in which to carry out bowing and felting.

- Seasonal sub-contracted felt making was permitted by hat making guilds at the time.

- The port of Lancaster crucially enabled trade around the coast of Britain and overseas.

- The demand for hats was growing from the mid eighteenth century onwards. This demand was not just for people migrating to growing industrialising towns and cities in Britain but also for Britain’s navy and army who had campaigns in Spain and America at the time. As this demand rose, hat production spread outwards from the town of Lancaster to nearby rural villages.

- Exports of hats from Lancaster were likely required by plantation workers and plantation owners in the West Indies. Plenty of pictures show plantation workers wearing hats, suggesting there was a regular demand in this part of the world. We have yet to find proof that hats made in the Lune valley were directly sold to plantations, but evidence that they were exported from Lancaster to the West Indies in general does exist. In December 1785 for example, the Rawlinson family owned ship Cavendish sailed to The Windward Islands with a mixed cargo including hats. The inventory of exports listed in the Rawlinson Voyage Book No.3 (1785-1789) reveals that William Braithwaite was sending 38 dozen seamen’s felt hats whilst George Braithwaite was sending men’s bound hats. Additionally, Chris Shearson was sending 40 dozen hats.

Sugar Cane Harvest, Jamaica, 1820s. From Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora.

Interestingly, on the same page of this document as the entry for Shearson’s quantity of hats is an entry for a consignment of furniture, namely mahogany desks and cases made in Lancaster by Robert Gillow. The mahogany trees used to make these would have been felled by enslaved Africans working in the West Indies; another thread in the complex tapestry of transatlantic trade and industry, colonialism and slavery.

This is why, if you pay a visit to the Maritime Museum soon, you’ll find our own felt hat exhibited alongside a Gillow grandfather clock in our Transatlantic Slave Trade gallery.

References and Further Reading

The Saturday Magazine, 10 January 1835; ‘The Manufacture of The Beaver Hat’; The Book of Trades or Library of Useful Trades, Vol. 1, 1811 (Wiltshire Family History Society); Andrew Ure, Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures and Mines (London 4th Edition, 1853).

Grant, Alison (1981). ‘Bristol & The Sugar Trade’. Longmans London.

Kerridge, Eric (1985). Textile manufacturers in Early Modern England 1500-1760.

Rawlinson, Abraham Rawlinson Voyage Book No. 3 1785-1789, from Lancashire Archives.

Workman, Christine (2000). ‘The Hat Industry’ Ch 6 pp 100-123 cited in Winstanley, Michael (2000) Rural Industries of The Lune Valley (Ed). Centre for North-West Regional Studies University of Lancaster, Carnegie Publishing Ltd.