Success

Sometimes it’s the least spectacular objects in our collection that have the most surprising stories behind them. This photo shows a wooden ship being refitted at Glasson’s graving dock. It’s labelled only as SUCCESS – Prison Ship. But a bit of research has turned up a world-spanning saga of trade, travel and showbiz; sinkings and salvage, fortunes and fire. Read on for the full story!

Built from teak in 1840 at Natmoo, Burma, the Success started life as a merchant ship trading around the coast of the Indian subcontinent. Before long she was sold to new owners in London and repurposed as a passenger vessel. She made three voyages carrying emigrants from Britain to Australia, and at least one taking indentured labourers from India to the Caribbean. (Slavery had only recently been abolished in the British Empire, and the indenture system was developing in its place to provide a continuing supply of cheap labour for the plantations.)

In 1852, at the end of her third voyage to Australia, the Success happened to arrive in Melbourne during the height of the Victoria Gold Rush. Her crew promptly deserted, hoping to make their fortunes in the gold fields. With no hope of hiring new hands, the owners decided to make the best of a bad job and sold the ship to the Government of Victoria for use as a prison hulk. (The local prisons were overflowing thanks to the crime and disorder that came with the gold rush.) The Success was not particularly successful in this role, however. There were several escape attempts and two murders on board – one of the victims being John Price, the local Superintendent of Prisons!

By 1860 the Success was used only for women and children prisoners, in the hope they’d cause less trouble. With the gold rush and the problems it brought coming to an end, she was soon converted into a stores ship and moored in the Yarra River for the next few decades.

After that, her story takes a curious turn. In 1890 she was sold to a group of entrepreneurs who converted her into a floating museum. Falsely advertised as a hundred-year-old convict transport ship, she was moored in Sydney Harbour. Visitors were charged for tours conducted by Harry Power, who had once been a prisoner on board. Previously known as Henry Johnson, he was born in Ireland but grew up in Lancashire. In 1840 he’d been convicted of theft and transported to Australia for a term of seven years. Like many convicts he remained there after his release, and went on to have an eventful career as a cattle-driver, bushranger and highwayman. Unfortunately his brief spell as a tour guide on the Success did not prove profitable. After less than a year the owners abandoned the venture and scuttled the ship. (Some versions of the story later claimed that it was sunk by a mob of local residents, angry at the exploitation of their ancestors’ stories.)

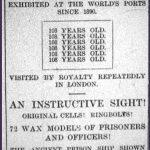

Despite the wreck’s position on the bottom of Kerosene Bay, the owners managed to recoup some of their investment by selling it on again. The following year the buyers refloated the Success and refitted her for another attempt at the same business. This one went better, and the ship visited Brisbane, Adelaide, Hobart, and once again Sydney, before heading to England in 1894. Advertised as an ‘ancient prison ship shown just as when in commission’, the displays included ‘wax models of prisoners and officers’, ‘original cells’, and ‘startling scenes’. The British appetite for dubious exhibitions of dark history was enough to keep the Success touring around our coastline for years.

In 1910 the ship changed hands again, and the new American owners planned to try their luck across the pond. For a seventy-year-old wooden sailing ship, a transatlantic voyage would be no mean feat, so a full refit was in order. The yard at Glasson Dock was an obvious choice for the job, positioned on the west coast and with a good reputation for building and repairing wooden ships. The Success was not only repaired and fitted with a wireless in preparation for the voyage but also re-rigged as a barquentine – a versatile sail plan with square-rigged sails on the foremast but fore-and-aft on the main and mizzen. Her departure was briefly delayed by difficulties in finding a crew, with several sailors claiming she was ‘haunted by the ghosts of dead malefactors’.

This delay proved fortunate for H D Smith, the General Manager of the company that owned the Success – he’d been intending to see her off before taking a berth on the Titanic for a more comfortable crossing! As it was, the Success didn’t set sail until the 15th April 1912, the same day the Titanic sank. A local newspaper article mused that ‘it will be something of an anomaly should this ancient craft arrive safely while the liner is lost’.

The Success sailed under the command of Captain John Scott, former commodore of a fleet of ships trading timber from Quebec. Besides the crew of nineteen, there was a Marconi wireless operator, two journalists from New York, and a Gaumont cinematograph operator who would make a record of the journey on film.

The voyage wasn’t easy. The Success had to contend with heavy gales. She was blown off course and at one point almost capsized. Where the Titanic had been expected to cross the Atlantic in six days, the Success took a full three months. The newly-fitted wireless came in handy when she had to call on the passing Cunard Liner Franconia for re-supply. Fortunately all wireless operators on transatlantic liners had been instructed by the Marconi Company to ‘keep a sharp lookout for the old vessel, and so minimise the risk of her voyage’. The Franconia passed by on no less than five occasions on her regular run between Liverpool and Boston, keeping in touch by wireless each time.

Despite the difficulties of the crossing, the Success arrived in Boston in mid-July and once again took up the role of a travelling museum. She toured the eastern seaboard and the ports of the great lakes for several years, and even ventured through the brand-new Panama Canal to be displayed at the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1915. She’s featured in a short segment in this film made by the Keystone Company (starting 10 min 20sec in.)

The ship changed hands several times during this period, and in 1917 was converted for commercial use as a cargo vessel – only to be sunk for the second time in her career the following year, this time by a collision with floating ice on the Ohio River in Carrollton, Kentucky. This was just a temporary setback though. She was soon refloated and returned to her previous status as an exhibition ship. In 1933 she was displayed at a second World’s Fair, this time in Chicago. That was to be her last great event, however. In 1940 the Success turned 100 years old, and by now she was beginning to show her age. Constant repairs were needed to keep her seaworthy and it was becoming uneconomical. A few years later she was sent to be broken up at Sandusky, Ohio. But before work could begin, a storm sank her at her moorings (for the third time!)

Even that was not quite the end of the story – there was still value to be had from that sturdy teak construction – and in 1945 a salvage operator raised the ship yet again and towed her to the nearby Port Clinton. Unfortunately the port proved too shallow for her to enter, and the Success was grounded just outside, never to be moved again. The following summer she was destroyed by fire. Hundreds of people lined the shore to watch this impromptu funeral pyre for the 106-year-old museum ship, but the cause of the blaze was never discovered.

Photo Sources

Main photo copyright Lancaster City Museums.

Others from:

(1) State Library of New South Wales

(3) Bute Museum